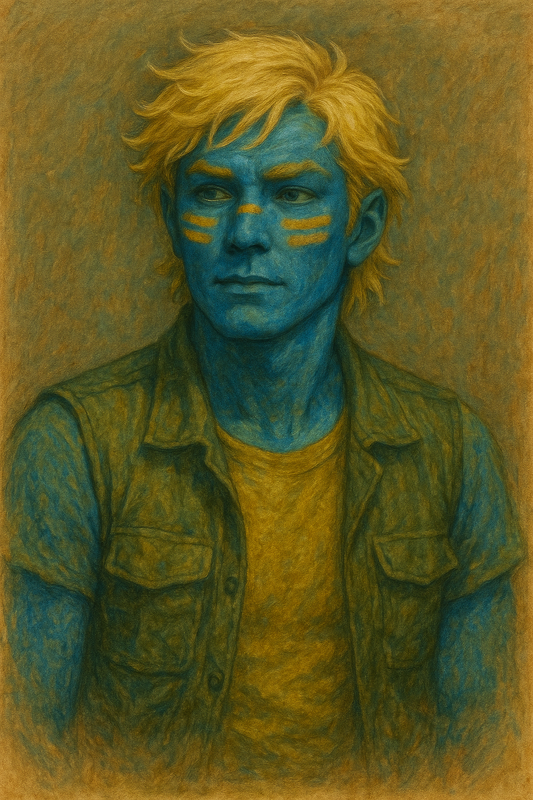

Korn "Neren" G. by Jpolter216

Species

Pantoran

Career

Smuggler

Specializations

Pilot, Racer (Sentinel)

System

Edge of the Empire

Edge of the Empire

5

| Threshold | 13 |

| Current | 0 |

| Threshold | 15 |

| Current | 0 |

| Ranged | 0 |

| Melee | 0 |

Characteristics

3

4

2

3

1

3

Skills

| Skill | Career? | Rank | Roll | Adj. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astrogation (Int) | X | 2 | ||

| Athletics (Br) | 0 | |||

| Charm (Pr) | 2 | |||

| Coercion (Will) | 0 | |||

| Computers (Int) | 0 | |||

| Cool (Pr) | X | 1 | ||

| Coordination (Ag) | X | 2 | ||

| Deception (Cun) | X | 2 | ||

| Discipline (Will) | 0 | |||

| Leadership (Pr) | 0 | |||

| Mechanics (Int) | 1 | |||

| Medicine (Int) | 0 | |||

| Negotiation (Pr) | 0 | |||

| Perception (Cun) | X | 2 | ||

| Piloting: Planetary (Ag) | X | 4 | ||

| Piloting: Space (Ag) | X | 4 | ||

| Resilience (Br) | 0 | |||

| Skulduggery (Cun) | X | 1 | ||

| Stealth (Ag) | 0 | |||

| Streetwise (Cun) | X | 1 | ||

| Survival (Cun) | 0 | |||

| Vigilance (Will) | 0 | |||

| Brawl (Br) | 0 | |||

| Gunnery (Ag) | X | 3 | ||

| Lightsaber (Br) | 0 | |||

| Melee (Br) | 0 | |||

| Ranged: Light (Ag) | 2 | |||

| Ranged: Heavy (Ag) | 0 | |||

| Knowledge: Core Worlds (Int) | 0 | |||

| Knowledge: Education (Int) | 0 | |||

| Knowledge: Lore (Int) | 0 | |||

| Knowledge: Outer Rim (Int) | 0 | |||

| Knowledge: Underworld (Int) | X | 2 | ||

| Knowledge: Warfare (Int) | 0 | |||

| Knowledge: Xenology (Int) | 0 |

Attacks

| Model 53 "Quicktrigger" Blaster Pistol |

RangeMedium |

SkillRanged: Light |

|

| Stun |

Damage6 |

Critical3 |

|

| Combat Knife |

RangeEngaged |

SkillMelee |

|

Damage+1 |

Critical3 |

||

| Sawed-Off Slug Thrower |

Range |

Skill |

|

Damage |

Critical |

5

350

10000

2

Weapons & Armor

Battle Vest: +1 soak, +2 soak when attacked by slug throwers or other physical projectile.

Heavy Clothing: +1 soak

Model 53 "Quicktrigger" Blaster Pistol (4HP)

Combat Knife

Sawed-Off Slug Thrower

Heavy Clothing: +1 soak

Model 53 "Quicktrigger" Blaster Pistol (4HP)

Combat Knife

Sawed-Off Slug Thrower

Personal Gear

Utility Belt

Tool Kit

Breath Mask and Respirator

Chance Cubes

Chiles-Zraii Foreman-Series Owner's Workshop Manual for YV-929 Light Freighter

2 Stims

Rhyol Whiskey Bottle (2)

Hutt Space Astrogation Chart

Pack of Low-grade death-stix

Camtono with 10K in credits.

Spacers Duffle

Parents Signed Fuel Manifesto

Kena’s Balosar Street Ribbon,

A six–seven inch woven pastel ribbon with Balosar-coded beads

Nal Hutta 22 wine

Fuax High-End Headdress/Head Piece

Tool Kit

Breath Mask and Respirator

Chance Cubes

Chiles-Zraii Foreman-Series Owner's Workshop Manual for YV-929 Light Freighter

2 Stims

Rhyol Whiskey Bottle (2)

Hutt Space Astrogation Chart

Pack of Low-grade death-stix

Camtono with 10K in credits.

Spacers Duffle

Parents Signed Fuel Manifesto

Kena’s Balosar Street Ribbon,

A six–seven inch woven pastel ribbon with Balosar-coded beads

Nal Hutta 22 wine

Fuax High-End Headdress/Head Piece

Assets & Resources

Sun Dress for Racer Girl, for our girl

Krevit John

Krevit John

Critical Injuries & Conditions

Talents

| Name | Rank | Book & Page | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Throttle | 1 | Edge Of The Empire Core Pg. 83 | Take a Full Throttle action: Make a HARD piloting check to increase a vehicles top speed by 1 for a number of rounds equal to cunning. |

| Skilled Jockey | 2 | Edge Of The Empire Core Pg. 83 | Remove Disadvantages per rank of Jockey from all piloting checks. |

| Galaxy Mapper | 1 | Edge Of The Empire Core Pg. 83 | Remove Disadvantages per rank of Galaxy Mapper from Astrogation checks. Checks take half normal time. |

| Let's Ride | 1 | Edge Of The Empire Core Pg. 83 | Once per round, may mount or dismount a vehicle/beast/cockpit/weapon station on a vehicle, as an incidental. |

| Grit | 2 | Endless Vigil Pg. 27 | Gain +1 Strain Threshold. |

| Free Running | 1 | Endless Vigil Pg. 27 | Suffer one strain when making a move maneuver to move to any location within short range |

| Shortcut | 2 | Endless Vigil Pg. 27 | During a chase, add ADVANTAGES per rank in Shortcut to any checks made to catch or escape an opponent. |

| Dead to Rights | 1 | Edge Of The Empire Core Pg. 83 | Spend one Destiny point to add additional damage equal to half Agility (rounded up) to one hit of successful attack made with ship or vehicle mounted weaponry. |

| Improved Full Throttle | 1 | Endless Vigil Pg. 27 | The character may voluntarily suffer one strain to attempt Full Throttle as a maneuver. In addition, the difficulty of Full Throttle is reduced to Average. |

Background

Korn never talked much when he flew, and that was usually the first thing people noticed about him. Pilots were supposed to curse, brag, scream, or sing as they punched through atmosphere. Korn didn’t. He flew the way a ghost might — quiet, fast, and with the unsettling sense that he was chasing something no one else could see.

From the outside, he looked like the kind of man holodramas were built around: striking even by galactic standards, sculpted in that unfairly symmetrical way Pantorans sometimes were. Most people assumed arrogance came with a face like that. But Korn walked through life with the subdued, half-lidded stare of someone who had long ago learned that beauty and worth were not related concepts. When strangers gazed too long, he’d simply turn away as if embarrassed to be in the body he’d been given.

Under cobalt skin and gold facial markings, he wore the expression of a man perpetually waiting for the punchline. Korn didn’t think himself special. He didn’t think himself particularly good. He existed with the practiced neutrality of someone who’d spent years believing he blended into crowds even while half of them turned to stare.

He was twenty-six. Or twenty-seven. Something like that. Even he wasn’t sure.

He went by Korn because that was all he remembered. His last name had begun with a G, he was almost certain of that, but the rest was gone — torn away by stormtroopers in white armor and a childhood that ended with a pair of parents screaming down a starship corridor. His mother’s last words had been, “Mommy will be right back.” Korn had learned early that “right back” was a lie adults told when they were about to disappear forever.

He’d been six years old when the Empire raided the Aurellia Loomworks freighter his parents ran. The first thing he did whenever he woke from night terrors — and he still had them, more nights than not — was look toward the door. Ten seconds of pure, crystalline hope. Ten seconds waiting for a woman who would never return. And then he’d touch his own face to check whether he was still a child. He never was.

He kept only one thing from that life: a yellowed, carbon-copy fuel manifest.

His parents’ signatures were at the bottom, faded but unbroken.

Korn carried it folded in his pocket like a wound he refused to let heal.

After the raid, he lived on the same freighter he’d been abandoned on. Dock workers, mechanics, and smugglers handed him cargo and credits on the simple logic that a living kid in a working ship was better than an empty hold with no pilot to move product. Korn didn’t know what he transported most days — and didn’t ask — but years later he’d realize the crates might have held anything: spice, weapons, corpses, or people. He only knew that moving freight kept him alive, and life had never taught him to question gifts.

He learned to read people the way most kids learn to read letters. A man’s shoulders told you what he wanted. A woman’s eyes told you if she was about to cheat you. Screaming meant danger; silence meant something worse. Adults rarely sheltered him. Yet some were kind in strange ways — a janitor sharing a sweetbread, a bartender asking nothing in return, a droid chirping a greeting that didn’t require emotional labor. Korn learned to float around these people, to drift in and out of small, temporary orbits. Never stay too long. Never attach. Never trust a goodbye.

When he was a teenager, he saw a pair of podracers get into a fight before a race. He watched mechanics pull them apart, watched security drag both pilots off the field, and watched two open cockpits sit waiting in the pit.

Korn slipped into one of them.

He won.

Security dragged him out of the pod by the collar. A Hutt rolled up moments later: Baladunda, young as Hutts counted years, slick-skinned and ambitious. Baladunda looked at Korn, looked at the smoking racer, and declared that the entire existing team was now fired. Removed. Executed, he later admitted without shame. Korn was the new pilot. Korn was Mabuki — my boy.

For thirteen years, Korn lived under Baladunda’s wing. The Hutt fed him, sheltered him, paid him fifteen hundred credits a week, taught him how to gamble without losing a hand, and kept him in the Outer Rim where Imperial warrants conveniently stopped at the edge of Hutt influence. Baladunda called him “my boy” often, but Korn eventually understood the truth behind the affection. A Hutt did not raise sons. A Hutt raised investments.

Still — Korn had been alone, and now he wasn’t.

The racing circuit never knew what to do with him. Some whispered he was a clone; others whispered he was a human wearing Pantoran makeup. More than once, a racer tried to rub the blue off his face. Korn would freeze, humiliated and stained by memories of hands that held him down, until Baladunda’s Gamorrean crew chief — Gungiligan — stepped in. Gungiligan was the closest thing Korn ever had to a father figure, though neither of them would say it aloud. Korn apologized to him in ways he apologized to no one else, usually through quiet gestures: a fixed hydrospanner, a sharper vibrofile, a bottle of something strong left on a workbench.

He flew with an intensity that made crowds roar and medics sweat. Korn pushed engines past tolerances, cut corners too close, dove too fast. He told himself the speed meant something. Told himself the cheers mattered. Told himself that if he flew fast enough, his mother might appear in the stands, arms open, ready to take him home.

But Korn learned that fame felt good only until the adrenaline faded. Then it was empty — the same way waking up beside a stranger was empty, the same way a Hutt’s applause was empty, the same way quick, hungry sex was empty.

Except once.

On Nar Shaddaa, long before the kill, Korn met a Balozar woman named Kena. She laughed at his awkward way of turning down a drink and mistook him for a fellow prostitute. He found that funny enough to laugh with her. When she asked — actually asked — if he wanted to come home with her, he said yes before he understood why.

It was the first time someone made love to him rather than took from him.

She vanished weeks later. Korn asked around. No one answered fast enough. A few died for it. Baladunda cleaned up the bodies and folded Korn closer into debt.

No reason, no comfort.

Just the reminder: If it weren’t for me, Mabuki, where would you be?

Korn didn’t sleep for days.

And then one morning he woke in his ship and found he had nowhere left to go.

He drifted toward a contract transporting a small mercenary group. They paid him for the job. Korn dropped them off at their destination, powered the ship down, and didn’t move for three days.

On the fourth day, the mercs knocked on the ramp and asked if he was leaving.

Korn started the engines.

He’d been with them ever since.

They didn’t ask about the kill during the race — though every major sports feed in the Outer Rim had replayed the footage. Korn, in the middle of a lap, pulled alongside a rival racer, extended a blaster, and shot the other pilot in the face. Ten thousand credits had changed hands off the record.

Korn carried those credits still, sealed in a camtono in his quarters. Sometimes he opened the case and stared at the bills while drinking until he passed out. He never spent a single one.

The mercenaries understood what Korn never said aloud:

they weren’t his first family,

but they were the first one that didn’t cost him something.

Korn liked bartenders, janitors, pit crews, mechanics — people who lived quiet lives and didn’t lie with their eyes. He liked droids because droids didn’t ask questions. He liked children because children saw him and didn’t flinch. Adults made him shut down; kids made him laugh. Give him a few children pretending to hijack an imaginary freighter and Korn would sit cross-legged, playing along. Bring an adult over to ask about cargo manifests, and Korn snapped back into the dull, flat stare of a man who’d forgotten how to breathe.

He feared goodbyes more than blasterfire. If someone told him they’d “be right back,” Korn assumed he’d never see them again. Better to cut the attachment early. Better to feel the sting now than the wound later.

And yet he still hoped — absurdly, stupidly, beautifully — that somewhere out there was one person meant for him. He believed that in the soft, fractured place in his chest he didn’t talk about.

He flew under the call-sign Colonel Four, a joke he made once and never bothered explaining: if he was “Four,” then people might assume there was a One through Three somewhere behind him. Maybe they’d leave him alone. Maybe they’d think he had backup. Maybe he’d even believe it himself.

In truth, Korn had never had backup.

But he had speed.

He had instincts.

He had a heart splintered into pieces he carried like shrapnel.

And he had a crew now — a real one — even if he didn’t know how to say it.

Some pilots fly to live.

Some pilots fly to win.

Korn flew because the galaxy had taken everything from him except the thrumming engines beneath his hands.

He flew because motion felt like life.

He flew because speed was the only thing that made the silence bearable.

He flew because a six-year-old boy was still sitting alone in a corridor, waiting for a door to open.

And sometimes, in the fraction of a second before a turn, Korn imagined that if he pushed the throttle just a little further…

…his mother might finally come back.

From the outside, he looked like the kind of man holodramas were built around: striking even by galactic standards, sculpted in that unfairly symmetrical way Pantorans sometimes were. Most people assumed arrogance came with a face like that. But Korn walked through life with the subdued, half-lidded stare of someone who had long ago learned that beauty and worth were not related concepts. When strangers gazed too long, he’d simply turn away as if embarrassed to be in the body he’d been given.

Under cobalt skin and gold facial markings, he wore the expression of a man perpetually waiting for the punchline. Korn didn’t think himself special. He didn’t think himself particularly good. He existed with the practiced neutrality of someone who’d spent years believing he blended into crowds even while half of them turned to stare.

He was twenty-six. Or twenty-seven. Something like that. Even he wasn’t sure.

He went by Korn because that was all he remembered. His last name had begun with a G, he was almost certain of that, but the rest was gone — torn away by stormtroopers in white armor and a childhood that ended with a pair of parents screaming down a starship corridor. His mother’s last words had been, “Mommy will be right back.” Korn had learned early that “right back” was a lie adults told when they were about to disappear forever.

He’d been six years old when the Empire raided the Aurellia Loomworks freighter his parents ran. The first thing he did whenever he woke from night terrors — and he still had them, more nights than not — was look toward the door. Ten seconds of pure, crystalline hope. Ten seconds waiting for a woman who would never return. And then he’d touch his own face to check whether he was still a child. He never was.

He kept only one thing from that life: a yellowed, carbon-copy fuel manifest.

His parents’ signatures were at the bottom, faded but unbroken.

Korn carried it folded in his pocket like a wound he refused to let heal.

After the raid, he lived on the same freighter he’d been abandoned on. Dock workers, mechanics, and smugglers handed him cargo and credits on the simple logic that a living kid in a working ship was better than an empty hold with no pilot to move product. Korn didn’t know what he transported most days — and didn’t ask — but years later he’d realize the crates might have held anything: spice, weapons, corpses, or people. He only knew that moving freight kept him alive, and life had never taught him to question gifts.

He learned to read people the way most kids learn to read letters. A man’s shoulders told you what he wanted. A woman’s eyes told you if she was about to cheat you. Screaming meant danger; silence meant something worse. Adults rarely sheltered him. Yet some were kind in strange ways — a janitor sharing a sweetbread, a bartender asking nothing in return, a droid chirping a greeting that didn’t require emotional labor. Korn learned to float around these people, to drift in and out of small, temporary orbits. Never stay too long. Never attach. Never trust a goodbye.

When he was a teenager, he saw a pair of podracers get into a fight before a race. He watched mechanics pull them apart, watched security drag both pilots off the field, and watched two open cockpits sit waiting in the pit.

Korn slipped into one of them.

He won.

Security dragged him out of the pod by the collar. A Hutt rolled up moments later: Baladunda, young as Hutts counted years, slick-skinned and ambitious. Baladunda looked at Korn, looked at the smoking racer, and declared that the entire existing team was now fired. Removed. Executed, he later admitted without shame. Korn was the new pilot. Korn was Mabuki — my boy.

For thirteen years, Korn lived under Baladunda’s wing. The Hutt fed him, sheltered him, paid him fifteen hundred credits a week, taught him how to gamble without losing a hand, and kept him in the Outer Rim where Imperial warrants conveniently stopped at the edge of Hutt influence. Baladunda called him “my boy” often, but Korn eventually understood the truth behind the affection. A Hutt did not raise sons. A Hutt raised investments.

Still — Korn had been alone, and now he wasn’t.

The racing circuit never knew what to do with him. Some whispered he was a clone; others whispered he was a human wearing Pantoran makeup. More than once, a racer tried to rub the blue off his face. Korn would freeze, humiliated and stained by memories of hands that held him down, until Baladunda’s Gamorrean crew chief — Gungiligan — stepped in. Gungiligan was the closest thing Korn ever had to a father figure, though neither of them would say it aloud. Korn apologized to him in ways he apologized to no one else, usually through quiet gestures: a fixed hydrospanner, a sharper vibrofile, a bottle of something strong left on a workbench.

He flew with an intensity that made crowds roar and medics sweat. Korn pushed engines past tolerances, cut corners too close, dove too fast. He told himself the speed meant something. Told himself the cheers mattered. Told himself that if he flew fast enough, his mother might appear in the stands, arms open, ready to take him home.

But Korn learned that fame felt good only until the adrenaline faded. Then it was empty — the same way waking up beside a stranger was empty, the same way a Hutt’s applause was empty, the same way quick, hungry sex was empty.

Except once.

On Nar Shaddaa, long before the kill, Korn met a Balozar woman named Kena. She laughed at his awkward way of turning down a drink and mistook him for a fellow prostitute. He found that funny enough to laugh with her. When she asked — actually asked — if he wanted to come home with her, he said yes before he understood why.

It was the first time someone made love to him rather than took from him.

She vanished weeks later. Korn asked around. No one answered fast enough. A few died for it. Baladunda cleaned up the bodies and folded Korn closer into debt.

No reason, no comfort.

Just the reminder: If it weren’t for me, Mabuki, where would you be?

Korn didn’t sleep for days.

And then one morning he woke in his ship and found he had nowhere left to go.

He drifted toward a contract transporting a small mercenary group. They paid him for the job. Korn dropped them off at their destination, powered the ship down, and didn’t move for three days.

On the fourth day, the mercs knocked on the ramp and asked if he was leaving.

Korn started the engines.

He’d been with them ever since.

They didn’t ask about the kill during the race — though every major sports feed in the Outer Rim had replayed the footage. Korn, in the middle of a lap, pulled alongside a rival racer, extended a blaster, and shot the other pilot in the face. Ten thousand credits had changed hands off the record.

Korn carried those credits still, sealed in a camtono in his quarters. Sometimes he opened the case and stared at the bills while drinking until he passed out. He never spent a single one.

The mercenaries understood what Korn never said aloud:

they weren’t his first family,

but they were the first one that didn’t cost him something.

Korn liked bartenders, janitors, pit crews, mechanics — people who lived quiet lives and didn’t lie with their eyes. He liked droids because droids didn’t ask questions. He liked children because children saw him and didn’t flinch. Adults made him shut down; kids made him laugh. Give him a few children pretending to hijack an imaginary freighter and Korn would sit cross-legged, playing along. Bring an adult over to ask about cargo manifests, and Korn snapped back into the dull, flat stare of a man who’d forgotten how to breathe.

He feared goodbyes more than blasterfire. If someone told him they’d “be right back,” Korn assumed he’d never see them again. Better to cut the attachment early. Better to feel the sting now than the wound later.

And yet he still hoped — absurdly, stupidly, beautifully — that somewhere out there was one person meant for him. He believed that in the soft, fractured place in his chest he didn’t talk about.

He flew under the call-sign Colonel Four, a joke he made once and never bothered explaining: if he was “Four,” then people might assume there was a One through Three somewhere behind him. Maybe they’d leave him alone. Maybe they’d think he had backup. Maybe he’d even believe it himself.

In truth, Korn had never had backup.

But he had speed.

He had instincts.

He had a heart splintered into pieces he carried like shrapnel.

And he had a crew now — a real one — even if he didn’t know how to say it.

Some pilots fly to live.

Some pilots fly to win.

Korn flew because the galaxy had taken everything from him except the thrumming engines beneath his hands.

He flew because motion felt like life.

He flew because speed was the only thing that made the silence bearable.

He flew because a six-year-old boy was still sitting alone in a corridor, waiting for a door to open.

And sometimes, in the fraction of a second before a turn, Korn imagined that if he pushed the throttle just a little further…

…his mother might finally come back.

Motivation

Self: What is his purpose. Where is the one in the galaxy out there for him?

Obligations

Servitude: Zero paid off my debt, but he said I owe him.

Description

5'10

Wiry pilot build + about ten lbs. muscle.

Wiry pilot build + about ten lbs. muscle.

Other Notes

Kena info from Matt: She has 1 warrant, posted on Onderon. Last location unknown. A more skilled person to access more features on guild bounty network. 3,000 credit bounty.

Bounty on me: 4,000 credits. Wanted alive.

The Mandalorian that hired me to take him to Cado Nemodia ended up bringing, either on purpose or not, a few more people. One of them is a Balosar known as "mother". I may have looked too hard at her when we first met. I mean nothing by it, but I am reminded of Kena. There is also a Doctor, who seems to have been mis-booked. I have no record of him filing or paying for a flight with me. He might be sent her by the Hutts the more I think about it. They have reaches all across the galaxy.

Tiny: One of the children that came aboard with the one called "mother", seems to be keeping an eye on me. Instead, we ate cookies together.

Bounty on me: 4,000 credits. Wanted alive.

The Mandalorian that hired me to take him to Cado Nemodia ended up bringing, either on purpose or not, a few more people. One of them is a Balosar known as "mother". I may have looked too hard at her when we first met. I mean nothing by it, but I am reminded of Kena. There is also a Doctor, who seems to have been mis-booked. I have no record of him filing or paying for a flight with me. He might be sent her by the Hutts the more I think about it. They have reaches all across the galaxy.

Tiny: One of the children that came aboard with the one called "mother", seems to be keeping an eye on me. Instead, we ate cookies together.